The US Supreme Court is fascinating. It has an almost mythological quality, with nine wise people passing their judgment wearing special robes. Knowledge about its functioning is not bland and faceless; it is highly personal, with the histories and personalities of each of The Nine being highly important.

In most countries there is not so much hubbub over the supreme court, and rarely do citizens even know anything about it. This is clearly different in the US. Why is this? I posit that it is because the US Supreme Court has taken on a role as effectual lawmakers. In other western countries their Supreme Courts mainly interpret the law, while in US the Supreme Court decides the law. This means that enormous power now resides with these nine non-democratically elected elders.

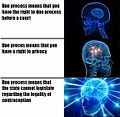

The easiest way to see this is by examining the Due Process Clause:

No person shall … be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.

That is it, the Due Process clause as written in the US Constitution. A straightforward reading is that it’s about that people should not get arrested or have their property confiscated without a trial and a ruling; a sensible law that is vital in separating a constitutional republic from a banana republic. But somehow the Supreme Court has latched onto this clause and given it as reason for a large variety of rulings. For example, in Pierce v Society of Sisters they ruled that the clause means that children cannot be required to attend public school; and in Griswold v Connecticut, two of the justices argued that this clause means that the state is not allowed to legislate regarding the legality of contraceptives. The galaxy brain level of this take is quite incredible.

No normal person reading the due process clause would think it applies to making legislation about contraceptives. If people are arrested or fined for these reasons without a proper trial, that would be in violation of due process. But how can making a law about contraception, that does not contain anything special about the process before a court, be in contradiction with due process?

Griswold v Connecticut is not a well-known case, but we could also look at Roe v Wade, the seminal ruling protecting the right to legal abortion. From Wikipedia: “In January 1973, the Supreme Court issued a 7–2 decision ruling that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provides a “right to privacy” that protects a pregnant woman’s right to choose whether or not to have an abortion.” This means that the justices are claiming that the the Due Process clause means that abortion must be allowed. Again, the Due Process clause in it’s entirety is: “No person shall … be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

People with whom I have discussed this have been quite surprised and skeptical. But it is easy to confirm for yourself on Wikipedia that this is indeed what the ruling says, and what the Due Process clause says.

It is worth noting that many other countries with a Supreme Court and a constitution have essentially the same clause, but without any history of using it in such judgments. They simple interpret it to mean that people have the right to due process before a court.

I am personally in favor of the right to use contraception, and the right to abortion. But herein lies the heart of the issue about the US Supreme Court: It’s about process vs results. Is the most important thing to have a well-designed process, or is the most important thing to get results that we like? Or more concretely: If they tend to make rulings that we agree with, do we want to be ruled by 9 non-elected Justices? Once they can interpret the Due Process clause as having an application so unrelated to its content, it is clear that the Supreme Court can make rulings unbounded by the content of the constitution. Rulings will instead be bounded by previous rulings of the Supreme Court, and the sense of the current Justices about what ought to be the law. As imagined, the system of government consists of a division between the legislative body that makes the laws, and a judicial body that interprets the laws made by the legislative body. But if the judicial body does not have to adhere to what is concretely written in the law, this division will be blurred, and the nine Supreme Court justices will in effect also make laws.

As I said, I think this is all quite obvious and easy to verify even for a layman. And of course, many justices have also pointed this out. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. put this forcefully:

I cannot believe that the Amendment was intended to give us [Supreme Court justices] carte blanche to embody our economic or moral beliefs in its prohibitions. Yet I can think of no narrower reason that seems to me to justify the present and the earlier decisions to which I have referred. Of course the words due process of law, if taken in their literal meaning, have no application to this case.

And a critique from Clarence Thomas:

By straying from the text of the Constitution, substantive due process exalts judges at the expense of the People from whom they derive their authority.

Having rulings not being based on the word of the law as such, can make it quite obvious in some cases that the law becomes based on the personal opinions of the justices. For example, take Obergefell v Hodges that establishes a fundamental right to marry for same-sex couples. This is again based partly on the Due Process clause. But if same-sex couples have a constitutional right to marriage, why not polygamous couples? There is clearly nothing in the sentence “No person shall … be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law” that means that something should apply to same-sex couples but not to polygamous people. The ruling is instead made on the basis of what these The Nine happen to think. (Or more precisely, the five of them who constituted the majority in this case.)

As I write this, there is a large political controversy about if a new justice will be nominated for the Supreme Court while Trump is still in office. This is important because conservative justices on the Supreme Court tend to vote more in line with the Republican Party. However, the reason for this is not mainly because their politics is Republican-leaning, but because they to a larger degree than liberal justices tend toward interpreting the law as written.

Liberal justices to a higher degree make rulings that do not follow the law as written, and thus break the distinction between the judicial and legislative branches. For this reason, if you support more liberal justices on the Supreme Court, you must stand by either:

The judicial-legislative distinction is not important, and its fine to have a system in which unelected judges essentially make the law, or

That the distinction is important; but it its worth it to make the legislative system worse in order to further the liberal cause.

It is my impression that this is rarely grappled with. Instead, conservative judges are commonly vilified as being bigoted and hateful. For example, I recall this video from the Daily Show, depicting Scalia as being saddened by the joy from the LGBT community over Obergefell v Hodges

Many people are in this way seemingly unable to grasp that Scalia saw his job as interpreting what the law says, not what the law ought to be. Probably this is partly because most people don’t realize how absent the connection to the actual words in The Constitution is.

I find it highly surprising how little this perspective is present in the public discourse. The discourse I’ve always heard is that there are liberal justices and conservative justices, just like there are liberal and conservative politicians. So of course you are on the side of the liberal justices if you support things like gay marriage. But from another perspective, the power in US has been partly usurped by this council of elders; and it’s hardly even discussed. It just becomes part of the all-consuming left-right dichotomy.

I am a big supporter of democracy and liberal values. And thus I think a superior system overall is where there is a sharp distinction between the judicial branch and the legislative branch, and where democratically elected people are the ones deciding the law. Things such as whether to ensure a right for same-sex marriage or abortion should be democratically decided, instead of by a council of nine elders. Then we would have a world where those rights do not come into jeopardy because an 87 year old lady died this year instead of the next.

The current way a lot of American progressives think of the Supreme Court only dates back to Brown vs. the Board. Before that the progressive left was actually deeply suspicious of judicial review (which Brown dramatically expanded).

I wouldn't say the trouble distinguishing between outcomes and process has to do with being left or right. Activists and the public across the spectrum tend to focus on the outcome. It has more to do with how the Constitution is romanticized into an expression of national identity. I think the reality is the actual text is often ambiguous and subject to more than one defensible interpretation (substantive due process being a great example).

Interesting stuff!